Katie McKinney | May 23

Tuesday, May 26 at 7p (CST) join us for a live, online-only edition of Polk’s America! Gray Rabbit:…

March 2, 2020 | Written by Thomas Samuel

In February’s Polk’s America lecture Douglas Shadle, Professor of Musicology at Vanderbilt’s Blair School of Music, introduced the crowd gathered at the Maury County Public Library to Anthony Philip Heinrich. Heinrich wrote grand, programmatic orchestral music based on naturalistic themes common in the early 19th century. Picture a musical James Fenimore Cooper or John James Audubon.

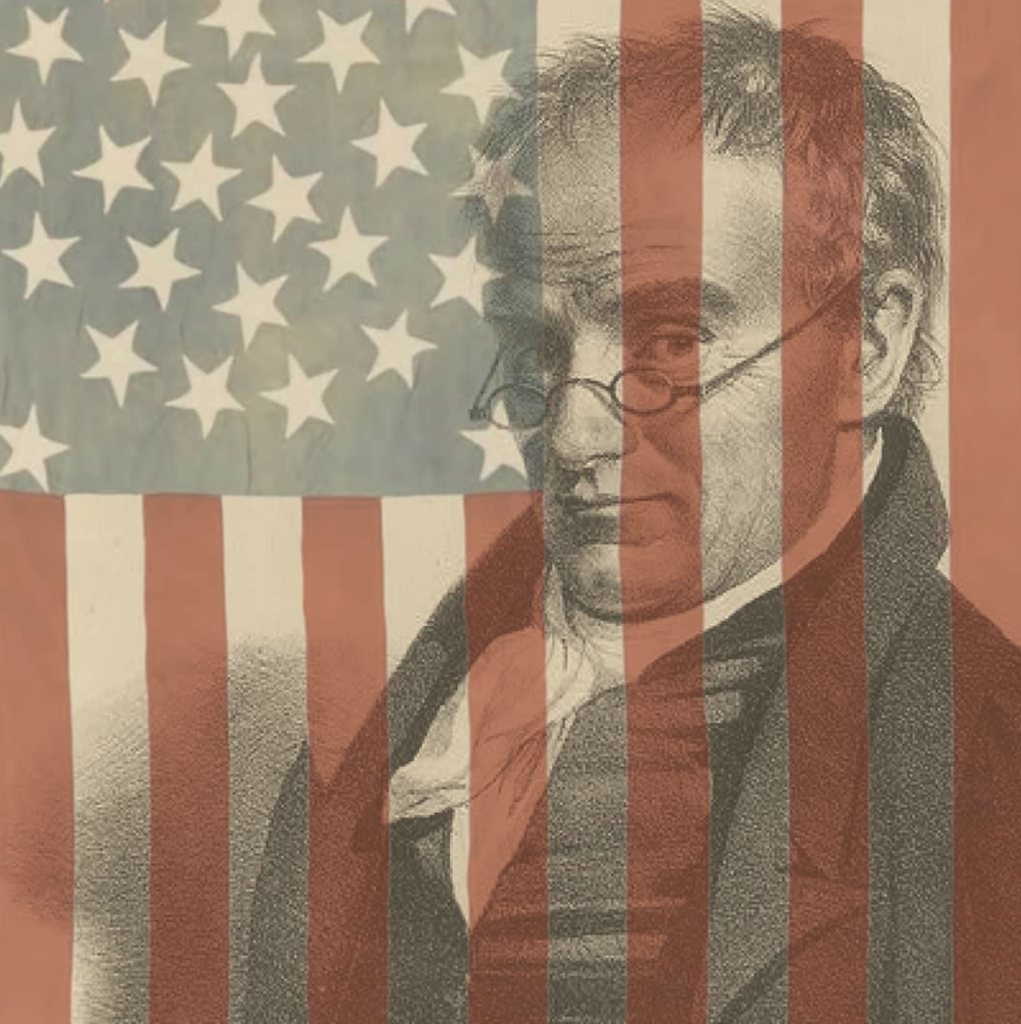

Born in Bohemia, A. P. Heinrich immigrated to the United States in an effort to expand a successful business initially started by an uncle, but the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and the ensuing economic upheaval left him penniless, stranded in Boston, Massachusetts. Directionless, the young Bohemian decided to pursue his first love, music.

Heinrich was inspired by his adopted country. The vast, natural beauty and the great promise of the west captured the budding musician’s imagination. Heinrich journeyed southwest on foot into the wilderness of Pennsylvania and then south along the Ohio River into the frontier state of Kentucky. Fittingly, he settled into a log cabin in Bardstown, KY on the property of a local judge and began to teach himself music composition.

Heinrich’s journey informed his writing. He billed himself as the Log Cabin Composer, living on roots and water on the American frontier. The truth was not so dramatic, his accomodations were comfortable and he had plenty to eat, but Heinrich wanted his image, like his music, to capture the spirit of frontier America. By 1820, he had completed his first collection, “The Dawning of Music in Kentucky.” Heinrich would go on to write hundreds of pieces of music including two full symphonies with titles like “The Columbiad, or the Migration of American Wild Passenger Pigeons.” However, like many early American composers, Heinrich and his music never really had a chance to flourish in concert halls across the nation.

During his time in Kentucky, Anthony Heinrich met another traveling artist. One whose work was also rooted in American naturalism. A man who created, arguably, one of the greatest American masterworks: John James Audubon. The two naturalists shared much in common. Both were immigrants who projected an image of frontier hardiness that was steadfastly American; both made art on a massive scale and in large quantities; and both struggled to gain notoriety in a young country whose industry, culture, and infrastructure were underprepared for the vision and scale of these ambitious artists.

Audubon relied on a subscription model to sell his work and initially had his “Birds of America” printed abroad before moving operations to the states as printing capabilities advanced at home. Heinrich, too, looked to Europe where there were large orchestras and capable musicians. However, even as interest in symphonic music began to grow in the United States, the Log Cabin Composer and his contemporaries found themselves cast to the wayside in favor of European composers like Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart.

In his 2015 book, “Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise,” Douglas Shadle examines the complex reasons composers like Heinrich never ascended into the pantheon of great American art. From underdeveloped orchestras to waves of rebellion in Europe in the 1840s to downright snobbery in the established orchestras in New York and beyond, many of the United States’ homegrown composers were never given an opportunity to find American ears.

Tuesday, May 26 at 7p (CST) join us for a live, online-only edition of Polk’s America! Gray Rabbit:…

Polk’s America w/ Alba Campo Rosillo Don’t miss this special, live & virtual edition of Polk’s America as…

Be the first to hear about new exhibitions, community events, and learning opportunities at the President James K. Polk Home and Museum.

© 2026 President James K. Polk Home and Museum